WHY PROOF?

Already in the 1400s mixing of gunpowder and alcohol was mentioned in the Nordics – alcohol allowed to bind and shape the dusty gun powder.

By the Mid-1500s gunpowder was used as a crude spirit measuring tool. Gunpowder soaked in strong whisky will ignite, whereas it will only fizz or not ignite at all if understrength. The term ‘proven’ and ‘proof’ became mainstay although the scale was rough – either it was proven… or not.

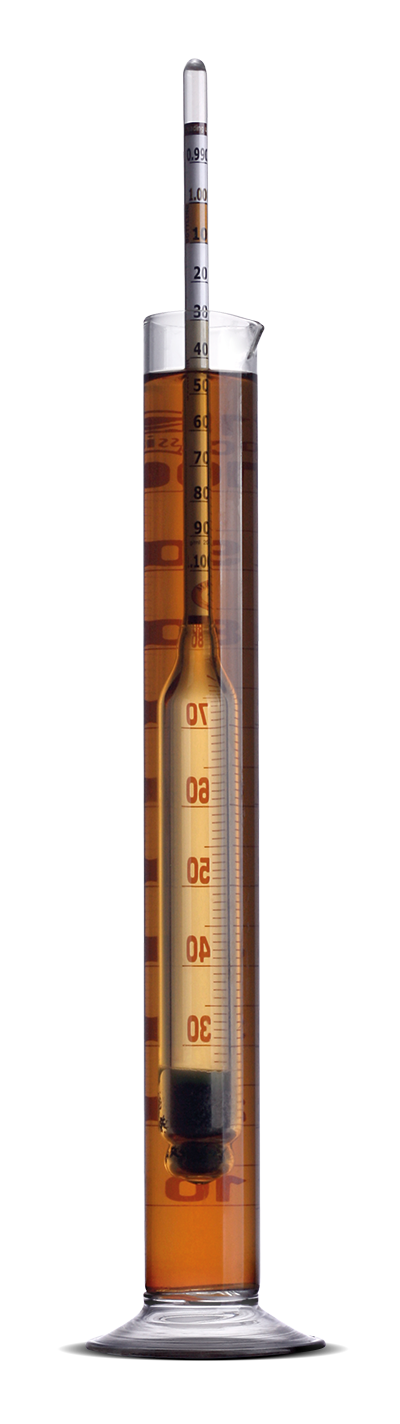

In 1816 the gunpowder test was officially abandoned in the UK for a new specific gravity test, that with the use of a hydrometer and thermometer could accurately read the strength of the whisky. This way of measuring is still in use, albeit from 1980 whisky is measured with the more logical Alcohol By Volume definition. Simply measuring the amount of alcohol in a bottle by percentage. If it states 40% alcohol – it means the rest is water (and approximately 0.1% are natural flavours).

The word ‘proof’ still exists on American labels. The measuring is not like the old complicated British way but in reality the same as the ABV…times two; i.e. 40% abv becomes 80 proof.

British Proof was much more complicated, but a simplified way to calculate the old British proof is times 7/4, i.e. 40% times 7 divided by 4… the result is 70 Proof.

This also means 100% pure alcohol equals 200 American Proof, but only 175 British Proof. Confused? That’s why we use ABV today.

But the hydrometer is still in use today at distilleries where it measures the alcohol content of the wash (or beer) before it is distilled. After distillation it is measured again and it aids the stillman finding the right cut points in order to select the heart (middle cut) of the spirit run.

We asked some retired customs & excise officers to describe their work with the proof and alcohol volume reading hydrometers. Although retired we have promised that they remain anonymous (the following names are made up – the stories are real).

SCOTT'S STORY

Each distillery officer had two hydrometers: one used daily and the other, or "Standard" was used weekly to compare with the "using" hydrometer to see how inaccurate the using hydrometer had become and a note made on the wooden case of the hydrometer of the result.

It was a serious offence to carry the hydrometer from warehouse to warehouse without it being in its protective wooden case. One officer did so but accidentally dropped the hydrometer resulting in serious damage. In an attempt to cover his mistake, he dashed into the office, grabbed the wooden case on his desk and then instructed a lorry driver to drive over it.

His intention was to explain to his superior that he dropped the case with the hydrometer in it and a lorry had crushed it before he could pick it up. Imagine his consternation when he discovered that he had grabbed the "Standard" from his desk and was now the guardian of two useless hydrometers.

THE STORY OF JOHN MILLAR

The proof hydrometer was in use until the end of 1979. It was a brass instrument approximately 20cm. long to which weights of different sizes could be attached and then immersed in a liquid along with a thermometer and by relating the readings to a book of tables, the specific gravity of the liquid could be found and thereby, in the case of whisky, the proof gallons contained in any particular cask could be calculated.

It was essential that the working hydrometer was measured against the standard hydrometer on a regular basis, usually weekly and I recall one warehouse complex where the manager was summoned on a Friday afternoon and set the task of providing the large double tube with a suitably aged whisky that would allow the Excise officer to use the heaviest weight, meaning that the whisky had been in cask for several years and the strength then reduced to that which would be potable and probably palatable as well.

The manager reappeared after a suitable interval and produced the tube of dark brown liquid for the officer to carry out his comparison. He tried the third heaviest weight with no success, then the second heaviest with the same result. Believing that he had been given the oldest whisky in the warehouse, he then attached the heaviest weight in the box. The result was the same: the hydrometer would not sink. The twinkle in the eye of the manager and his wide grin revealed the truth:- he had filled the double tube with cold tea in the belief that the officer had the intention of taking a well matured whisky home for the weekend. As if he would!!

IAN MOSS

In the seventies and eighties, we only had one distillery to look after, occasionally two. We would sometimes meet for lunch at Towiemore, a distillery just outside Dufftown, that had been closed for centuries, but was still used for warehousing. Here we had built a putting green so we could practice our putting and if we needed driving practice during office hours the best place was Knockdhu Distillery where some of my colleagues had sewn yeast bags together and hung them in one end inside a disused building.

The tee was at the opposite end. Perfect place to practice my swing.

Of course, our day job was making sure all spirit and whisky was accounted for, but the distillery boys were also colleagues and it was necessary to keep a good working relationship. This could be aided by allowing them time to measure strength of maturing whisky, i.e. a little taster. I held one key and the head warehouseman would hold the other, and only together could we enter into a warehouse. On occasions I would let the warehousemen know that I would go for a smoke, allowing them the time it took to smoke a cigarette by the door (this was before all the health and safety rules) to “test” the whisky. Therefore I can honestly say that I have never witnessed anyone removing any whisky - nor have I ever smoked.

But on Friday afternoons or Saturday mornings, yes we used to work till noon on Saturdays, I requested a sample, a litre or so, of mature whisky to be delivered to my office. This was required to test or calibrate the hydrometers. I never once used new make spirit to test my equipment, but preferably well mature whisky that had been near a sherry cask. Much like the WaterProof style. My colleagues all did the same in the area and we all used to meet at a pub in Dufftown to exchange stories and whisky.

MORE FROM JOHN

The distillery officer was aided by a Revenue Assistant who was tasked with watching the warehouses and ensuring that the casks being moved tallied with the paperwork. These RA’s were often retired military personnel and a lot of their time was spent watching and waiting.

To relieve the boredom, one RA took it upon himself to bring back the lustre to the hydrometers which had acquired a patina of malt whisky during their years of use. He lovingly polished the working and standard hydrometers with Brasso rendering each gleaming; resplendent; useless. The weight of the instruments had been so radically altered by his action that neither was capable of measuring the specific gravity of the spirit.

The brass hydrometers became redundant on the first day of January 1980 when the industry and officialdom went metric. Out went proof gallons and brass hydrometers and in their place came litres of alcohol and a set of glass hydrometers housed in a foam-lined briefcase which looked remarkably similar on the top and bottom sides. One officer discovered to his dismay on the first day of use that a small label indicating TOP would be a sensible addition when he inadvertently opened the briefcase upside down and six brand new glass hydrometers went crashing to the floor. Ooops!!!!!

AND FINALLY

The final tale involves a former colleague of John, Scott and Ian. He was in charge of a warehouse next to a bottling hall.

The whisky arrived in casks all of which had to be “dipped and tried” which involved dipping the thermometer and hydrometer into a tube of whisky in order to find the strength of the spirit and hence calculate the proof gallonage in order to ensure that none had been abstracted during the voyage from across Scotland.

Each time he dipped his fingers into the whisky, he licked them dry and, as there were 200 casks, it involved quite a lot of licking. Unfortunately, on his way home in the rain a car drove out of a side street without warning and collided with his car.

As he felt he was not to blame, he thought that intervention from the police would be a suitable course of action. Even more unfortunately, the police breathalysed both drivers and he was found to be over the legal limit of alcohol and was subsequently charged with drunk driving and he lost his licence for a year… just because he had been licking his fingers… 200 times.